Alchemy: The Science of Transformation

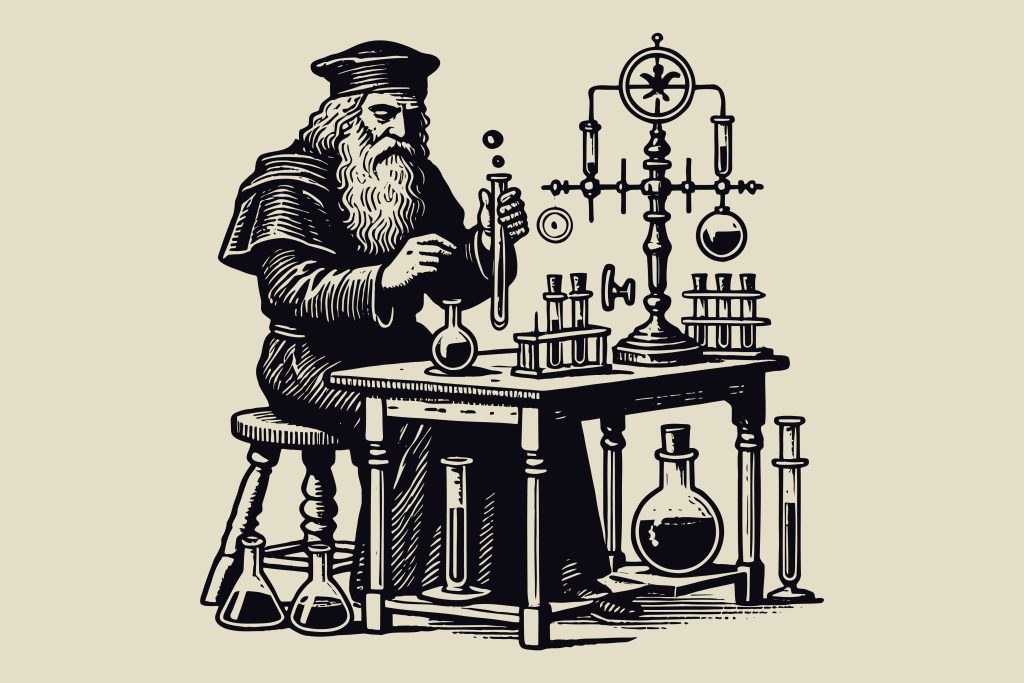

Alchemy is often imagined as a secretive art, sages hunched over flasks and furnaces in dim chambers, whispering incantations in pursuit of gold or immortality. Yet beneath the cloak of mystery lies a deeply philosophical and spiritual discipline, one that wove together the threads of early science, mysticism, and metaphysical inquiry. From Ancient Greece to Islamic scholarship, from medieval Europe to Renaissance occultism, alchemy has long stood at the crossroads of material and spiritual transformation.

Much of Western alchemy’s philosophical foundation can be traced back to Aristotle. Though many of his scientific theories were later disproven, his influence was profound. In his Meteorologica, Aristotle proposed that metals and minerals formed through the compression of vapours rising from the earth, a theory that would shape alchemical thinking for centuries. Even more influential was his theory of the four elements—earth, air, fire, and water—which became a cornerstone of alchemical cosmology. By fusing Egyptian practical knowledge with Hellenistic philosophy, Aristotle inadvertently laid the groundwork for an enduring alchemical worldview. This foundation was expanded upon by Islamic scholars, most notably Geber (Jabir Ibn Hayyan), who is often considered a father of alchemy. His Book of the Composition of Alchemy introduced the revolutionary mercury-sulphur theory, which posited that all matter was composed of these two fundamental principles in varying proportions. While much of his work survives only in fragments, his ideas were brought into Europe through Latin translations, particularly that of Robert of Chester in 1144. These translations not only preserved alchemical knowledge but helped to spark Europe’s own intellectual revival. Geber’s writings, dense and enigmatic, gave rise to the term “gibberish”—a nod to his complex, symbolic style that veiled deep truths beneath layers of metaphor. Symbolism, in fact, became a defining feature of alchemical texts. To protect their knowledge from misuse—and perhaps to preserve the sacredness of the discipline—alchemists often encoded their writings with symbolic language known as Decknamen. These allegorical codes meant that substances like “tin” might represent entirely different materials or concepts, depending on context. This cryptic nature rendered alchemical instruction both tantalizing and impenetrable, encouraging seekers to read not only with their minds but with intuition and spiritual insight.

As the tradition matured in medieval and Renaissance Europe, it absorbed local legends and mythologies. One of the most enduring figures to emerge from this blend of history and myth is Nicholas Flamel, a French scribe whose fame rests on the legend of the Philosopher’s Stone. Though likely exaggerated, stories tell of Flamel discovering a mysterious book filled with alchemical symbols and, through its guidance, transmuting base metals into gold and achieving immortality. Such tales, though unverifiable, speak to the aspirations that defined alchemy: not merely the transformation of matter, but the elevation of the soul and the discovery of eternal truths.

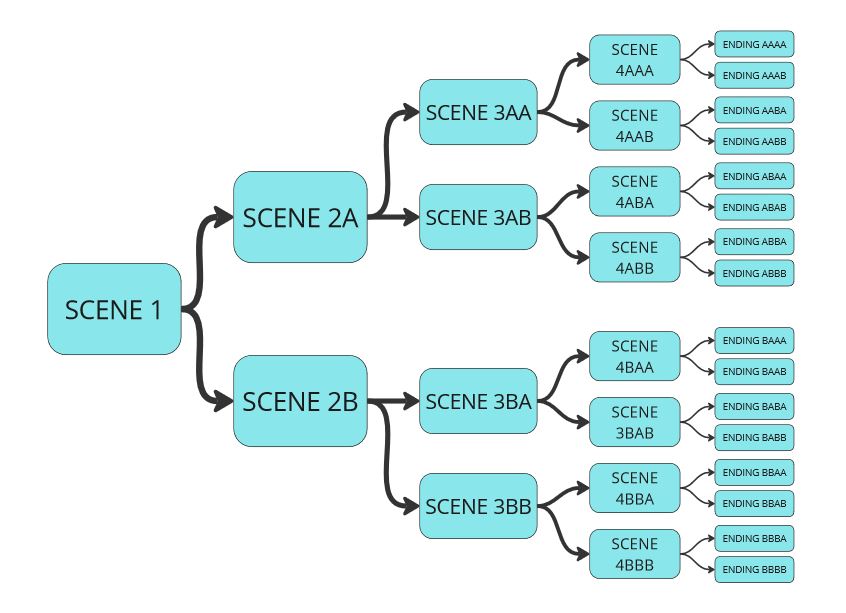

The Philosopher’s Stone, central to these legends, became the symbol of the Magnum Opus—the “Great Work” of alchemy. It was said to grant immortality, rejuvenation, or the power to turn lead into gold. But just as each alchemist had a slightly different vision of the Stone, the path to it was also veiled in symbolism and spiritual allegory. Alchemical illustrations, often impossible for laypeople to interpret, encoded instructions for internal and external transformation. The pursuit of the Stone, then, became a metaphor for the transformation of the self: a journey toward purification, perfection, and unity with the divine. This sacred transformation was guided by key philosophical principles. Alchemists believed that all things originated from a divine source and shared a vital force that animated both the material and spiritual worlds. Life, matter, and consciousness were deeply interconnected, and the alchemist’s task was to study and amplify this divine spark. Nature, to them, was not static but striving toward perfection—and humanity, endowed with reason and spirit, had the power to aid this evolution. By aligning with the laws of the universe, the alchemist could not only transform lead into gold but awaken their own latent divinity.

To express this process, alchemy identified three essentials—Mercury, Sulfur, and Salt—not as mere substances, but as fundamental principles of all creation. Mercury represented the spirit, the fluid potentiality from which all things arise. Sulfur stood for the soul, the dynamic force of identity and transformation. Salt, by contrast, embodied the body—the solid, enduring structure that held spirit and soul together. These three formed a trinity of becoming, mirroring the alchemist’s task: to awaken the spirit, harness its energy, and manifest it in the material world.

Complementing this triadic model were the four classical elements—Fire, Water, Air, and Earth—which together shaped the fabric of existence. Fire initiated transformation, both life-giving and consuming. Water nurtured and dissolved, enabling growth and change. Air harmonized opposites, carrying energy between realms. Earth grounded the ephemeral, giving form to the alchemical process. These elements, in balance with the three essentials, created a universal map for transformation, guiding the alchemist in both laboratory experiments and spiritual contemplation. The alchemical tradition also gave rise to strange and wondrous ideas, such as the creation of the homunculus—a tiny artificial human. This concept, popularized by Paracelsus, suggested that through secret processes, one might produce a being capable of astonishing feats. While fantastical, the homunculus symbolized the alchemist’s desire to emulate divine creation, blurring the line between nature and artifice, and echoing the deeper pursuit of mastery over both the seen and unseen worlds.

Alchemy, in all its complexity, represents the meeting of two worlds: the material and the spiritual, the physical and the philosophical. It is the art of transformation in every sense—of metals, of selves, of consciousness. Through the centuries, it has served not only as a precursor to modern chemistry but as a sacred discipline, reminding us that true change begins within. In seeking to perfect the world, the alchemist ultimately seeks to perfect the soul.